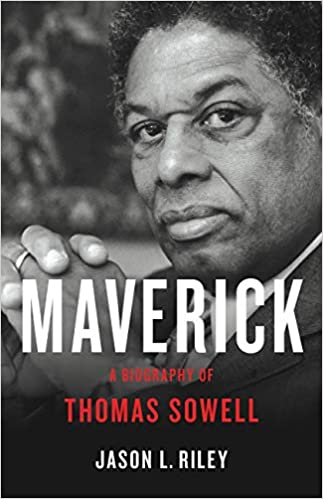

In an effort to bring Sowell’s background and insights back into the national consciousness, Wall Street Journal columnist Jason Riley wrote Maverick: A Biography of Thomas Sowell.

Thomas Sowell is a one-of-a-kind thinker, scholar, and commentator. Through his more than 50 books on subjects including economics, race, and intellectual history, Sowell has established himself as a premier American mind over the past half-century. In an age where sloppy thinking with a side of muddled messaging is the standard fare in our national discourse, the life and work of Thomas Sowell can serve as a reminder of what the gold standard of political and policy analysis looks like.

In an effort to bring Sowell’s background and insights back into the national consciousness, Wall Street Journal columnist Jason Riley wrote Maverick: A Biography of Thomas Sowell.

In an easily digestible 250 pages, Riley does not merely teach the reader the facts about Sowell’s life and accomplishments, but shows why Sowell is such a unique figure and details the substance of some of Sowell’s most important contributions to our political and intellectual conversations. In this vein, the book can broadly be split into two sections. The first section — chapters one through four — illustrates “Sowell’s go-it-alone attitude”; the second — chapters five through eight — is a deep dive into an array of issues Sowell has tackled throughout his career.

What Makes Sowell a Maverick?

Properly defined, a maverick is someone who is “unorthodox or independent-minded.” Whether it be in academia or the intellectual landscape more generally, Riley makes it clear that one would be hard-pressed to describe Sowell in any other way.

While a professor at some of the nation’s most prestigious schools — including Cornell, UCLA, and Amherst — Sowell exhibited a teaching style that most had left behind in the 1950s. He was demanding; he was no-nonsense; he didn’t accept goofing off in class or buy excuses for missing a test unannounced.

Riley uses some truly engaging anecdotes to demonstrate this fact. The most striking example is when Sowell tells a student that he had to leave the economics program at Cornell because he was persistently disruptive in class and ill-prepared despite several warnings. The chairman of the Cornell economics department did not back Sowell’s decision, and the two argued bitterly for over an hour, Riley wrote. The argument ended with Sowell saying, “You have my resignation — from the program and from Cornell University.”

Sowell has turned down teaching offers from schools such as Stanford, Dartmouth, and the University of Wisconsin. He has also pulled a book from a publisher and returned the advance after the company insisted on revising “800 AD” to “AD 800.” All of this goes to show that Sowell has always been his own man, never simply going along to get along. This was best exemplified when Riley writes, “He was a contrarian who didn’t much worry about burning his bridges. He was an independent thinker who welcomed rhetorical combat.”

This has not only been true in the academic world, but also in the greater intellectual world. Riley details the willingness of Sowell to tackle subjects that few others would touch, his willingness to challenge others when he believed they got something wrong, and the many attacks — often dishonest ones — from the mainstream media on his work.

In Maverick, Riley also does a masterful job of linking Sowell’s attitude and actions throughout his career to his time at University of Chicago, where he learned their signature approach to economics from famed economists George Stigler and Milton Friedman. This approach was described as “more concrete, less abstract; more pragmatic; less speculative.”

He does not only approach questions without regard for prevailing narratives, but he also makes economic concepts uncharacteristically easy to grasp through his use of practical examples.

On top of an approach that emphasized empiricism, the program was extremely demanding. It was noted in the book that while Harvard’s economics program brought in 27 doctoral students and 25 graduated, University of Chicago brought in 70 and only 25 graduated. In short, it was an intense, no-nonsense environment.

One can see the influence that the University of Chicago had on Sowell every time they read one of his works. He does not only approach questions without regard for prevailing narratives, but he also makes economic concepts uncharacteristically easy to grasp through his use of practical examples.

Sowell’s Intellectual Contributions

While recognizing how unique Sowell is as a person is important, we should not lose sight of the crucial contributions he has made throughout his career to the political, policy, economic, historical, and intellectual conversations of our time. Riley has described this book as an intellectual biography, and there is no doubt that he has succeeded in bringing Sowell’s ideas into the spotlight.

In chapters five through eight, Riley examines some of Sowell’s most important ideas and books, beginning with Knowledge and Decisions, moving on to his informal trilogy on “visions,” and later detailing his writings on civil rights and his “culture” trilogy.

While each of these chapters are different when it comes to particular content, they have a common thread connecting them. No matter what subject it is on, Sowell has forwarded the conversation with groundbreaking research or reasoning as well as made complex topics accessible to laymen. In Knowledge and Decisions, for example, a book Sowell published in 1980, he took F.A. Hayek’s fundamental observations about the diffuse nature of knowledge in a society and not only made the concept more accessible for the average reader through real-world examples, but also “broadened the application” of the initial principles, Hayek himself wrote.

He does not only talk about economics; he does not only talk about race; he does not only examine history. Rather, one of the things that makes Sowell so unique is that he not only writes about all those subjects, but has the ability to seamlessly weave them together — using economic thinking to evaluate things such as race, history, and culture.

While that is only one example, it can be repeated for any number of his dozens of books — and Riley makes that crystal clear. Sowell is not a one-trick pony. He does not only talk about economics; he does not only talk about race; he does not only examine history. Rather, one of the things that makes him so unique is that he not only writes about all those subjects, but has the ability to seamlessly weave them together — using economic thinking to evaluate things such as race, history, and culture.

Takeaways

Both the breadth and depth of the insights Thomas Sowell has shared with the world through his works are nearly unparalleled. That we have had the ability to learn from him for so long is something that should be appreciated.

In Maverick, Riley succeeds in giving Sowell the recognition he deserves. And, in the end, Riley should be commended for bringing Sowell’s insights to the forefront in a time when we need them more than ever.

Review of Maverick: A Biography of Thomas Sowell (Basic Books, 2021), 304 pp.

Jack Elbaum

Jack Elbaum is a Hazlitt Writing Fellow at FEE and an incoming sophomore at George Washington University. His writing has been featured in The Wall Street Journal, Newsweek, The New York Post, and the Washington Examiner. You can contact him at [email protected] and follow him on Twitter @Jack_Elbaum.

This article was originally published on FEE.org. Read the original article.